Governor Gavin Newsom made a significant announcement on High Speed Rail during his State of the State address:

Some say that he’s stopping high speed rail, but clearly he doesn’t intend to stop whatever’s being built on the ground. Is he somehow against high speed rail altogether? I don’t think so. Some people think that Newsom should just continue the project as originally planned, but considering the difficulties over the last decade a “timeout” is long overdue.

What is clear is that according to the current high speed rail business plan, it would require far more funding and would take much longer to complete. It would require a significant commitment, not only from the current generations of politicians, but from the future generations a decade or two to come. It is just a matter of time that someone hits a pause button.

Without new funding sources, the state would have to divert funds from existing transportation projects.

But more than that, the high speed rail project has several barriers due to some longstanding unresolved issues.

Prop 1A language

Prop 1A, the ballot measure that enabled the high speed rail project, is unusual that it contained several “performance measures” that specified the travel time. While on one hand it appears like a marketing language in a car brochure about the vehicle’s capability, it also placed constraints because the only way to amend a language in a ballot measure is with another ballot measure, or unless a judge agrees that what the authority is doing still somehow complies with the ballot measure. As a result, the project suffered a series of lawsuits. Entities that disagree with the authority can take the issue to the court and drag the lawsuit for years to come.

Voters were told that the high-speed trains would hit 220 mph, get from Los Angeles to San Francisco in two hours and 40 minutes, operate without subsidies and obtain funding and environmental clearances for entire operating segments before construction.

https://www.latimes.com/local/la-me-bullet-train-battle-20140609-story.html

It was the state legislature that drafted the Prop 1A language and the High Speed Rail Authority that endorsed it. Why would the state and the agency commit to a requirement that they cannot fulfill? The reason is that there are different visions among the legislators and HSRA board members regarding high speed rail. Some people, like Quentin Kopp, who was the chairman of the HSR Authority during the time when Prop 1A was drafted and placed on the ballot, believe that high speed rail should be a dedicated, segregated system similar to Japan. On the other hand, other high speed rail supporters believe in a European version of the trains where high speed trains can share tracks with local trains.

That dispute wasn’t settled even well after Prop 1A was approved. In 2009, the authority released a 4 track segregated plan for the Peninsula Corridor. Kopp believed in a 4 track segregated plan as it would clearly meet the performance goals as required by the Prop 1A language, but many local cities, who have endorsed Prop 1A when it appeared on the ballot, thought high speed rail would be blended with Caltrain. They wouldn’t have supported the ballot measure if they had known that a 4 track system was planned.

The 2009 plan met with huge resistance from the communities. A blended system compromise was reached and approved by the state legislature, but it was challenged in court from those who do not want to see any infrastructure improvement on the rail corridor.

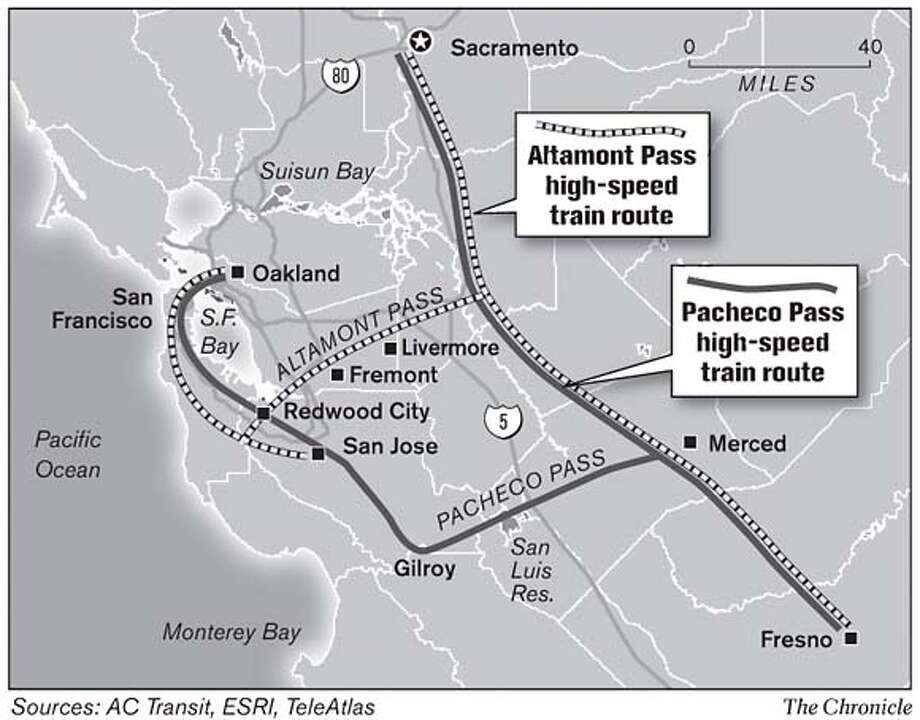

Altamont vs. Pacheco

The alignment between the Bay Area and the Central Valley has also been a long ongoing struggle, despite the fact that Pacheco has been a designated high speed rail corridor for years even before Prop 1A was drafted.

The advantages of the Altamont Corridor:

- Shorter travel time from San Francisco to LA than Pacheco.

- It is along an established rail corridor over the Dumbarton Rail Bridge and Altamont Pass.

- San Jose would be served by a line from Fremont to San Jose, while it would take longer to LA but would be shorter to Sacramento if line to Sacramento were built.

- Able to serve more of the Bay Area commute-shed such as Tracy and Modesto and get the line closer to Sacramento.

The advantages of the Pacheco Corridor:

- Shorter travel time from San Jose to LA

- Would operate along the entire length of the Caltrain corridor. Every train to/from SF would go through San Jose, rather than be served by a branch.

- Get the line closer to the Monterey Bay Area.

Led by Rod Diridon, a long time High Speed Rail Authority board member, the San Jose interests were able to convince the agency to select the Pacheco alignment and drop the Altamont Pass from further consideration. They like the idea of having Diridon Station be a hub along the main line and not a terminal of a branch line. Those who support the BART extension from Fremont to San Jose would have one less potential competition.

Although the board approved what the San Jose leaders had wanted, the project still faced difficulties in San Jose especially in the alignment just south of the Diridon Station. The performance criteria set by Prop 1A didn’t help as the current Diridon Station isn’t big enough or straight enough. Much more expensive and disruptive solutions were proposed including an underground station crossing an underground BART alignment.

The HSR Authority, still recognizing that the Altamont is still a key commute corridor, funded a separate study to improve the Altamont Pass to become a feeder corridor to the High Speed Rail system, but the project has gone nowhere after the initial study. Although the concept has support in the San Joaquin County where it is a part of the Bay Area commute shed, it has little support in the Tri-Valley and the Silicon Valley, where they focus on extending BART.

Grapevine vs. Tehachapi

Although not as controversial as Altamont vs. Pacheco, the selection of the Tehachapi pass is not without detractors. The Authority chose the Tehachapi pass because of the political support from the desert communities (a commute shed for the Los Angeles area). Also by routing through the desert, it could be a link for rail line to Las Vegas.

But none the less the Tehachapi pass appears to be a detour compare to I-5, and especially in light of the performance criteria set by Prop 1A. Also the Tehachapi pass requires the line to go through Bakersfield. Although High Speed Rail proposed a station in Downtown Bakersfield as policy recommended, its operational demands require a much bigger footprint that is incompatible with a quiet, conservative city. The rail authority had to reconfigure its plan to avoid downtown.

What could be salvaged?

Rail supporters and many HSR critics agree that whatever is being built must be finished. But is the end product be a train from nowhere to nowhere? With proper planning I think it is possible to have an end product where trains can serve the Bay Area and/or Sacramento that is faster than Brightline, a “high speed rail” line in Florida, or Acela in the East Coast. It may not be Japan, but it could be more like Europe if not America.

The state has ordered locomotives and railcars for its Amtrak fleet that are the same as those used by the Brightline in Florida, all produced by Siemens in Sacramento. They will have the capability to operate at 125 mph.

Currently the Amtrak San Joaquin trains go to Sacramento and Oakland. These trains can operate at high speed on HSR tracks and at conventional speed outside of HSR tracks, but still provide direct service.

There are already projects to improve rail corridors in the upper San Joaquin Valley area to extend ACE and improve Amtrak service, which include ACE extension as far as Merced, where the current phase for high speed rail construction is supposed to end. Also in a rare move, Union Pacific made one of its rail corridor between Stockton and Sacramento available to passenger rail.

In previous business plans, they talked about some kind of coordinated service upon the completion of the 1st HSR segment in the Central Valley. However the concept is vague and has gone nowhere beyond showing up on the documents. This is time to address it.

Construction of the initial operating section of High-Speed Rail is planned to be completed in 2018. This initial section of tracks will be put to use immediately upon completion and deliver early benefits by allowing the existing San Joaquin route to operate on the new tracks until the initiation of full High-Speed Rail service. With creation of the “Northern California Unified Service,” the San Joaquin route, ACE, and Capitol Corridor trains will be enhanced and operated in a more integrated manner, creating an improved network reaching from Bakersfield to the San Francisco Bay Area and Sacramento.

State Rail Plan FAQ http://www.dot.ca.gov/californiarail/docs/130130_csrp_faq.pdf

Once everything is done, it would up to future voters and future politicians to decide where to build and where to improve. The mistakes written into Prop 1A would no longer hamper them.

I think Newsom understands that High Speed Rail should be done differently, but at this current political environment it is hard to continue commitment given the constraints set by Prop 1A. If the idea is to provide new funding or make big changes to the program, he would have to get voter approval, which wouldn’t be feasible until there’s something to show, some train running somewhere. So I agree that the priority is to get the Central Valley segment done. Newsom’s announcement may seem to be a mixed message whether you’re for or against high speed rail, but for me his intention is crystal clear. The flaw of Prop 1A is that it requires the state to be perfect in its execution, but it is being weaponized by those who don’t want us transitioning to a green economy, and we cannot allow them to have that.