I am troubled with the plan to reduce VTA’s transit operating budget. For a long time now VTA has not been playing in a relevant role in reducing traffic or provide a transportation alternative in a region that is suffering from housing shortage and increasing traffic congestion.

For many years, Silicon Valley business and political leaders have been pushing for sales taxes to increase transportation funding, but at nearly all instances VTA proposed and enacted service reduction within a few years after a tax is approved. Meanwhile, some of the same local politicians come out and declare that their city is not able to accommodate more housing because the city has no transit. It appears that while taxpayers are generous, there is no serious effort in improving mass transit, and subsequently be used as an excuse for inaction.

Basically for the past 20 years VTA is a BART construction agency with running buses and light rail as a side business. I do not share the same faith as many of the VTA board members have that extending a unique wide gauge subway system (and taking money away from other transit priorities) will somehow cause a transit revolution in the Silicon Valley. It is ironic that the San Jose mayor (also sits on the VTA board) is inviting the Boring Company to come up with a low cost solution for a fixed guideway link between the Diridon Station and San Jose Airport, because VTA does not have enough funding to make the connection on its own, but insists on VTA to fund a multi-billion large bore tunnel for BART.

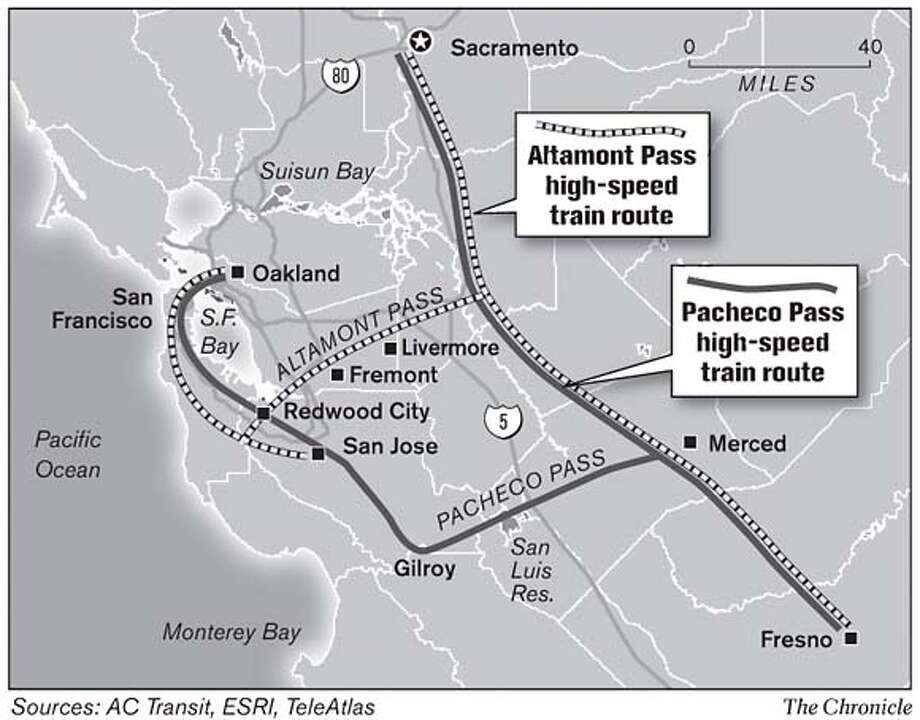

By observing trend across regions, transit usage and transit oriented developments grow when basic transit services increase, such as in Seattle, as well as pursuing lower cost solutions for rail. The eBART line in Antioch demonstrated lower cost and superiority of standard gauge rail technology while preserving full connectivity with the old BART system (good enough to appear as a single continuous line on the BART system map). If the valley leaders had listened, we would’ve had a rail around the bay many years already.

I am not in favor of the 90-10 service allocation. Many “service increases” in the plan would add runs at the margins (like early morning or later in the evening), or slightly boosting all day frequency. I do not believe that productivity of re-allocated services would necessarily be improved. Today, VTA can tell the communities that they’re removing unproductive routes from transit starved areas as service reallocation. What would stop VTA in the future to reduce service that were initially reallocated because productivity hasn’t improved? This appears to be a bait and switch in an attempt to diffuse resistance to general service cuts. It would be a easier sell to reduce service from 7 minutes to 10 minutes on line 500 a few years later than to eliminate an entire route in the suburbs as a strategy to cut transit funding.

On that basis, I am not in favor of eliminating line 22 overnight service and the Almaden light rail line. I am also not in favor of cutting the Blue Line to Baypointe. The Orange Line should only operate during the peak. At other times, the Blue and Green lines should operate as it is presently. I believe that there would be more interest for a rail to rail connection between BART and Downtown San Jose via a single light rail ride on the Blue Line than to the west via the Orange Line.

I would suggest that VTA should drop the express fare entirely. VTA staff indicated that the express routes are not productive because of the lack of seat turnovers, and that the express routes also experience high cost per rider and low farebox recovery compared to local routes.

By dropping the express fare category, express routes would be able to accept local passengers and provide them with additional options. For example, riders from Morgan Hill to Gilroy in the afternoon can board line 168 buses in addition to line 68 buses operating on the same street.

Many agencies implement higher fares as a zone surcharge, but VTA’s surcharge is a speed premium than a distance/zone premium. After BART is opened, all of the express routes would be entirely within Santa Clara County, and would be covered by VTA’s local service (but would take longer, or may be a transfer or two).

In light of the social-economic inequality and long distance commutes endured by many of the low income residents, along with the complexity of implementing a multi-tiered fare scheme, it would be a wise policy of eliminating the express fares entirely. I believe it would have little financial impact on VTA but can significantly improve productivity and improve transit experience. Low income riders can board whichever bus that will get them faster, rather than boarding the local bus for a long trip because they cannot afford the speed premium. Express routes could be redesigned to better connect with local service or even substitute some of the local service to enhance coverage.

Rather than cutting the transit operating budget, VTA should look elsewhere to address its financial issues, and particularly look into its project priorities. For many years we heard a lot of excuses why transit hasn’t work or wouldn’t work in the valley but nothing much about improving it or make any serious commitment to it. From time to time you see VTA taking on new initiatives (micro-transit or BRT) but often VTA walks away and let them die when the agency encounter slight difficulties. This “BART-above-all-else” and “nothing’s-worth-doing” attitudes are extremely discouraging to many transit, environmental, and sustainable development advocates like me who could and should be VTA allies, not critics.